If you went off the grid in 2010 and re-emerged to survey the cast of characters in today’s business pages, you might be forgiven for thinking that things hadn’t changed.

Bob Iger is still the CEO of Disney. Julian Dunkerton runs Superdry, and Richard Bradbury is in charge of River Island. There’s Nittin Passi at Missguided and, if you’d looked in late 2022, even Howard Schultz at Starbucks.

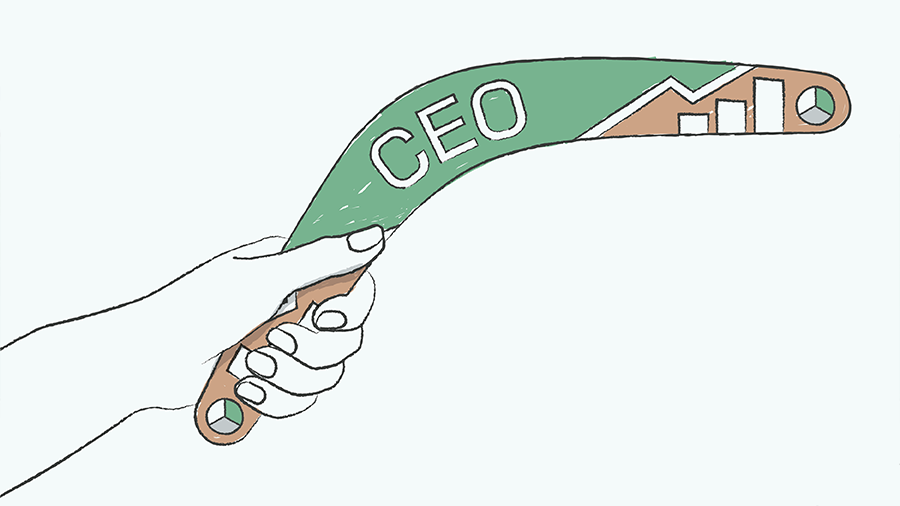

Each left their firm for a time, voluntarily or otherwise, only to return later, brought back by boards or investors hoping they could restore some lost magic.

Founders and former CEOs aren’t the only ones we’re seeing return to their old stomping grounds. More and more, we’re noticing company veterans come back in more senior roles, after years elsewhere.

Matalan CEO Jo Whitfield comes to mind (she worked there from 2002-8) as does Peter Ruis, who returned to run John Lewis department stores this year after leaving as brand director in 2013.

Statistically, it makes sense that we’d see more bounceback leaders as job tenures contract — there’s just a higher chance that an opportunity would bring you back through those same doors.

But it also makes sense for the business itself. Former executives already know the business — its strengths and weaknesses, how it works, where the bodies are buried — making organ rejection less likely.

And there is no one safer to choose to run a business than someone who ran it successfully before — hence the return of the aforementioned founders.

At the same time, time apart means a returning CEO candidate can often bring fresh ideas and experiences to the table that most internal hires cannot.

This is perhaps less likely with someone like Iger, who was retired, than someone like Whitfield whose career took her to other places like Asda and Co-Op. But even then the distance can help people to see the business differently.

The downside

It can look like the best of both worlds, but there are risks to hiring a bounceback CEO. Former leaders in particular may not appreciate how the business has changed.

The wrong bounceback hire may simply look to apply old solutions to new problems, rejecting beneficial innovations that postdate their departure. This in turn can create challenges with people who’ve joined the business in the interim, in stark contrast to the dream team that the high-achieving CEOs likely relied on in their glory days.

I can’t help but think of Bjorn Borg’s ill-fated comeback to tennis in the early 1990s, complete with now-naff bandana and wooden racquet: the game had moved on, and he lost every match.

The board’s duty

There are two lessons. The first is for management: treat people well on the way out, at every level, because one day the company may want to hire them again.

The second is for the board, which plays a crucial role here. Particularly when the business is struggling, the board may want someone who can restore the company’s confidence, by recalling the vision that made it shine in the first place.

But they also need to know that the returning executive shares their essential understanding of the business and its situation today, and is going to apply fresh ideas too.

Either that, or they hire the old CEO back in an interim capacity, while they figure out carefully who they need to take the company in a new direction, as Starbucks did with Schultz.

In other words, when the board hires a bounceback CEO, it can’t just be because they can’t think of anyone else.

And if the company has struggled in the years since a former leader left, then they need to think very carefully about why that is, and whether bringing the same person back is going to solve the problem.

Ultimately, boards need to consider leadership in the round, so that when their bounceback CEO leaves for the second time, the company has the culture and leadership pipeline to thrive without them.

Find the best candidate for your key leadership positions, whether they’re returners or making their first appearance at your door. Talk to us now about your executive search options.