So in early 2021 he did what so many founders in his position have done, and listed it.

So in early 2021 he did what so many founders in his position have done, and listed it.

The IPO, set at £5.4bn, was one of the biggest in London in recent years. The shares held their value at first but, beleaguered by short-sellers and press stories suggesting it had been overvalued, they began to collapse later in the year, at one point losing nearly 90% of their value.

THG wasn’t alone. Later in 2021 Deliveroo had what the FT called the worst IPO in London’s history, with shares losing a quarter of their value on the first day of trading – they’re now over 70% down on listing price.

Moulding, who said the whole process “sucked from start to finish”, argues that the problem here isn’t listing in general, but the peculiar behaviour of the London market in particular. It may be that the NASDAQ could be a more hospitable environment for high-growth British companies that want to raise finance on the public markets.

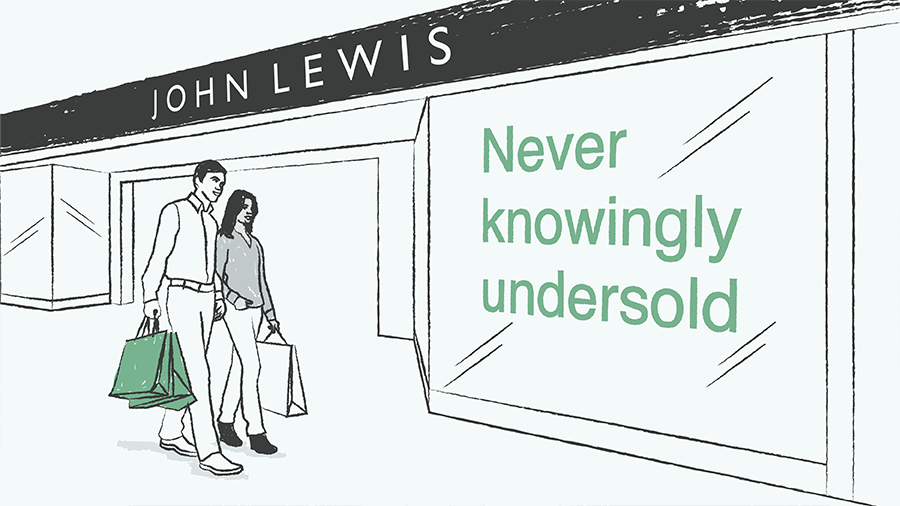

Yet there is also an essential risk baked into the IPO process, simply because the investment banks that prepare the prospectuses are incentivised to build a register that supports a high flotation price, which in turn encourages the kind of short term investor who wants to make a quick buck.

This raises a deeper question about the desirability of going public: are you prepared for the shareholders you’ll get? You can’t choose them, once the stock is on the open market, and although you might hope for institutions with long-term horizons, you might end up with hedge funds, activists or a gaggle of Reddit meme-stock day traders.

You’ll also no doubt have to confront a good deal more attention, which may or may not be unwanted. Listed CEOs have several times confirmed to me what every private business CEO has long suspected, that it’s intensely distracting to have to keep looking over your shoulder at the share price, when what you want to do is grow the business.

Indeed, one FTSE 250 leader confessed that the prospect of entering the FTSE 100 was particularly daunting because of the added scrutiny.

Scrutiny is not a bad thing of course – in principle and in moderation. But if everything you do gets dissected by equity analysts, proxy advisors and media pundits, you can easily slip into the habit of second-guessing yourself.

Whether an IPO is right for you obviously depends on what you want, as a founder. If it is simply to exit, cash out and move on, then it may be the best option.

If it’s to bring the company to mega-scale, it might be the only option – there are patient investors who can push a private business to vast heights, but no one’s that patient. They will eventually want an exit, which means that unless you are so profitable that you can keep bootstrapping your own growth ad infinitum, you’ll need some finance from outside.

Indeed, there is a credibility to listing on the stock exchange that you can’t get otherwise. For a private business to have a large valuation and the backing of superstar venture capitalists like Andreesen Horowitz, Sequoia or SoftBank is undoubtedly impressive, but it’s still a measure of potential rather than actual value. It’s what those investors think you will be worth when they – and you – exit, not before.

So we won’t see founders turning their noses up at the public markets anytime soon. But if you intend to keep growing the business, just make sure that you’re ready for the change that an IPO can bring.