Taken individually, each could be seen as a one-off, temporary blow from which the grand economic force of globalisation would recover.

Yet taken together, they constitute a formidable and possibly lasting threat. Political populism, which in the West sees globalisation as a devious scheme to outsource jobs, shows no sign of dissipating. America’s stance towards China hasn’t softened meaningfully despite President Biden’s election.

The pandemic may be – hopefully – drawing into its final phases, but it is hardly over. China is still pursuing a zero Covid strategy, which means if someone sneezes in Guangdong they shut the port for two weeks.

Even if that policy changes, the past two years have just taught a generation of business people a lesson about resilience and the vulnerability of complex supply chains that they will never forget. The events in Ukraine will only have reinforced this point. No one will assume reliability on a macro scale as they did before.

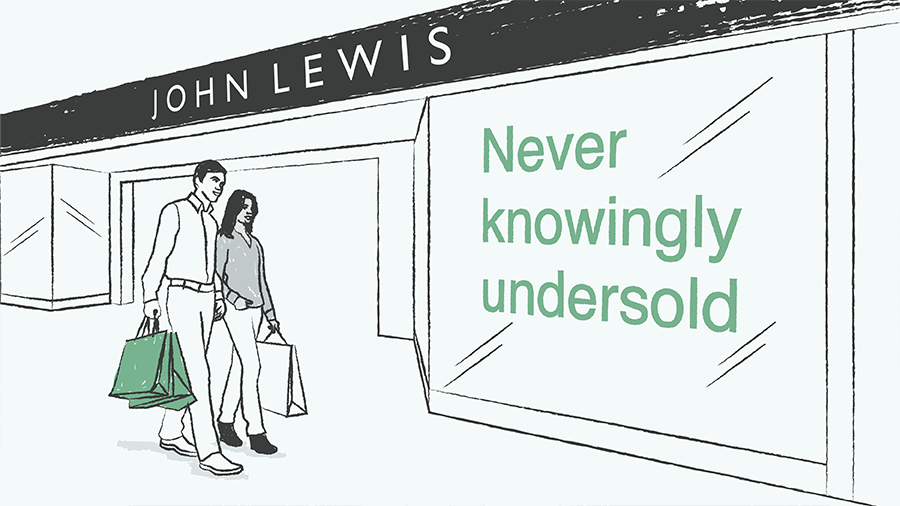

There are other reasons why businesses might be turning their backs on certain parts of the world. Much of our cotton comes from Xinjiang, for example, where the plight of the Uighur people has left fashion and retail businesses stuck between taking a stand for their values – and their customers’ values – and having lucrative operations cancelled by an irate Chinese state.

The choice for Western firms in Russia is clearly starker, but it’s the same kind of situation. Moral outrages in far off or not-so-far-off parts of the world can no longer be ignored because they’re inconvenient to your bottom line.

What will be the consequences of all this? We haven’t yet seen a mass exodus of Western businesses from China (Russia’s a different story), or indeed any dramatic simplification of multinational supply chains. The economics currently don’t add up – it’s still much cheaper to source globally.

What we are seeing is businesses paying a lot more attention to their geopolitical vulnerabilities than they used to. ‘Global pandemic’ and ‘war in Europe’ don’t seem so far-fetched anymore when you’re reading lists of global risks.

This in turn is incentivising diversification (which incidentally isn’t new when it comes to cotton; the only reason Egyptian cotton is so widespread is that the American Civil War disrupted supply from the Deep South) and simplification.

The next decade or so may therefore be characterised by a retraction rather than a reversal of globalisation, into regional pockets or among groups of allies, where the risks seem less.

China may lose a lot of ground to pro-business Indonesia or perhaps to North Africa. Russia could end up completely isolated – even from the European gas and energy markets, which exposes a whole new area of previously unseen vulnerability.

Then again, maybe globalisation will recover, if we just have a few ‘normal’ years in a row, and everyone will remember 2016-2022 as an era of aberrations. The future remains as uncertain as ever.

What’s changed is that now we have been forcibly reminded that politics, war and obscure bat viruses can have just as great an impact on the fortunes of businesses as can grand economic forces or the brilliance of individual leaders. The best we can do is to approach the world with eyes open to the risks as well as to the opportunities.