*Originally published Nov 2020, updated Aug 2021

The Greeks ditched the idea of the flawless hero at least 2,500 years ago, and not just because it made for bad fiction. Real people inevitably make mistakes, even if they don’t always recognise them.

For some reason though, we still gravitate towards the ideal, from Churchill to Jobs, of the uniquely talented figure who sticks to their guns, who believes in themselves when no one else does, and who is ultimately proven right.

That’s why it’s so hard to admit you’re wrong as you’re a leader. When you’ve invested your reputation as well as your resources into a strategy, then backtracking seems to imply weakness and ineptitude.

Often, the opposite is true. It takes courage and self-awareness to make strategic U-turns, so long as they’re not too frequent or made for the wrong reasons, not least because you’ll likely take a lot of flak for it. We’ve seen that recently with Joe Biden’s decision to pull American forces from Afghanistan – it’s a horrible situation, but the rapid Taliban takeover seems to vindicate his suggestion that the US would have had to remain there indefinitely to achieve its strategic aims.

As psychologist Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic wrote in his 2013 book Confidence, the problem emerges because we tend to confuse competence with self-confidence, even though they are completely separate things.

Most people, he wrote, are not as good at their job as they would like to believe: ‘People see themselves as better than average across virtually any domain of competence – for example, cooking, sense of humour, and leadership – even though, by definition, most people are average.’

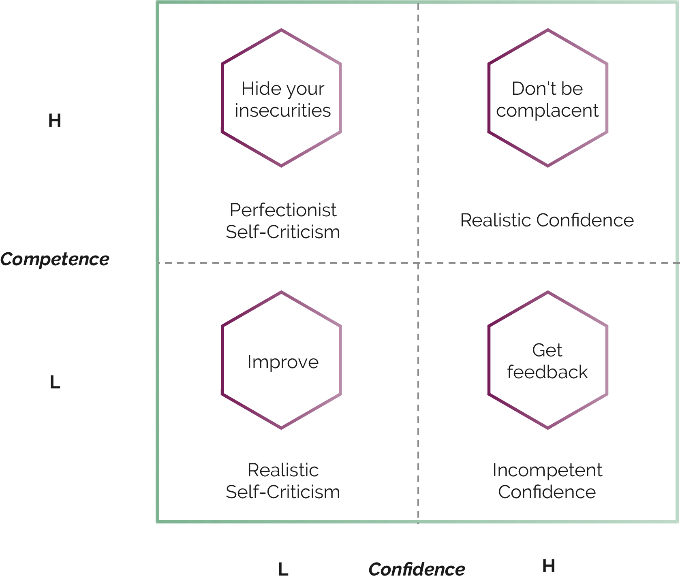

Chamorro-Premuzic created the confidence-competence matrix (above) to explain this link. While some of the most effective people fall into the high competence, low confidence category – they are generally humble and self-critical enough to listen to dissenting opinions and seek constant improvement – the majority fall instead into the high confidence, low competence category.

These people are complacent – they believe that they are already great at their job and yet they fail to take feedback and lack the work ethic to become genuinely competent. You often see them applying for roles they don’t have the necessary skills for, exuding self-belief, impressing their interviewer sufficiently to land the job, and then inevitably getting the sack, though not always before dragging the company down with them.

It’s even worse when they get to leadership positions. At the heart of so many underperforming businesses lies an incompetent, overconfident leadership team, creating a toxic culture where anxious, alienated workers practise counterproductive work behaviours as they jostle for position. Consider that the economic impact of avoiding a toxic worker is two times higher than that of hiring a star performer, then multiply that to the level of the C-suite.

How can we solve this problem within businesses?

As a starter, those (like us) who assess leadership candidates need to improve their ability to distinguish between confidence and competence. At ORESA we have dedicated much of the past few years to fine-tuning our approach and distinct methodology for assessing leaders. The result: 98% of candidates in place after 12 months and four years of average tenure – a very good ROI for our clients.

The traditional interview format sometimes only tests a candidate’s ability to embellish their own skills and career, allowing them to overshadow stronger but less gregarious characters, but that doesn’t mean we’re fated to hire style over substance. At ORESA we believe that both qualitative and quantitative data are required and that a deep holistic approach ensures an accurate assessment of aptitude. This is imperative especially when, in our view, leaders need to demonstrate a balance of humility and self-belief.

How can we address this in ourselves?

On a personal level, it’s important to recognise that some confidence is important – excessive self-doubt can be highly counterproductive – but equally that there’s a point beyond which greater confidence becomes detrimental. We need to take a step back to examine how often we find ourselves ‘faking it’ rather than admitting that we’re out of our depth.

Then take some time to understand your environment and whether it rewards overconfidence. Company structures and cultures that encourage toxic competition inevitably reward employees who learn to shout louder than their colleagues. It’s important therefore to reinforce to your rising stars that with leadership power comes a responsibility to support those junior to you, rather than blindly concentrating on climbing higher.

Remember also that, as the Greeks well knew, success can become the seed of hubris. As Chamorro-Premuzic wrote: ‘The more successful and powerful you are, the more that people will suck up to you, even when they think poorly of you.’ We can all learn a lot by actively seeking constructive criticism, and by taking it on board. Few employees have the confidence to criticise their boss, but encouraging an open channel of good and bad feedback is one way for us all to stay self-aware.